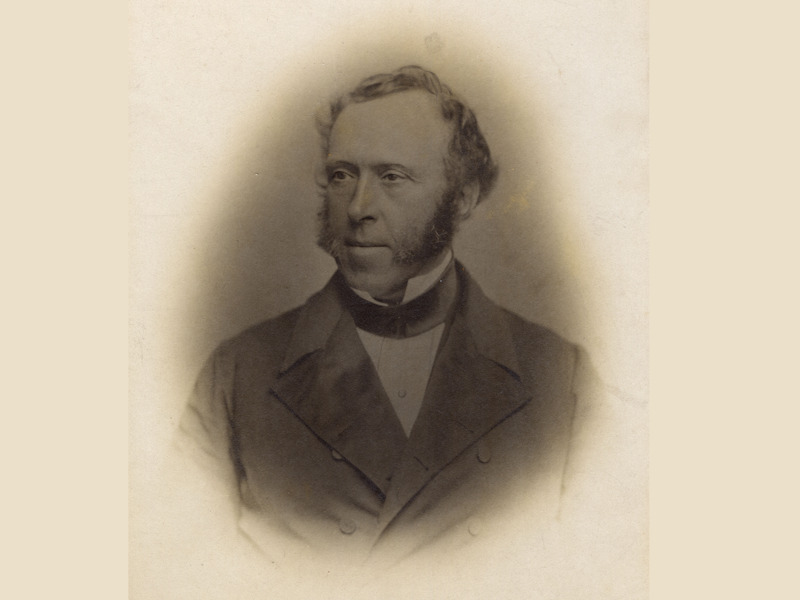

James Braidwood

James Braidwood was a fire service trailblazer. He was one of the first professional firefighters in the UK, becoming a leader in his field. He established an excellent reputation for his training methods and successful leadership of the Fire Engine Establishment in his home city of Edinburgh, before coming to London in 1832.

Early days

James Braidwood was born in Edinburgh in 1800, as the tenth child of Janet Mitchell and Francis James Braidwood. He was educated at Edinburgh High School. Braidwood’s father was a skilled cabinet maker, but he also appears to have had interests in the building trade. He first worked with his father as a surveyor, and learned much about the structure of buildings which helped him in his later profession as a firefighter.

Master of Fire Engines

After Edinburgh suffered several serious fires the city council decided to create the Edinburgh Fire Engine Establishment in 1824. James Braidwood was appointed as the Master of Fire Engines at only 23 years of age. He led a team of part-time firefighters to provide 24-hour cover for the city.

Only three weeks later a challenging fire broke out, known as the Great Fire of Edinburgh. Five hundred people were made homeless and many lives lost.

The devastation caused became proof that greater investment was needed in the fire service to protect the city. The authorities and the fire insurance companies agreed to divide the expenses needed for Braidwood to be able to train his firefighters, establish more effective ways of tackling fires and to have access to the best equipment possible.

Shaping the Scottish fire service

In 1830, Braidwood wrote a book outlining training for firefighters and the equipment they needed to do their job effectively. In this, he was likely the first person to write about the subject in a detailed way.

Braidwood's tactics and methods were considered a success. He had insisted on weekly training for his firefighters, provided a gym for them and ensured the best equipment for fighting fires was available. His leadership also focused on the best practises for operating in the narrow streets of Edinburgh. He also understood the strategic importance of positioning fire stations in the best locations to respond to fires.

“If there were any circumstances to cause unusual apprehension Braidwood went into the burning premises himself: he never sent his men where he would not go.”

The Fireman magazine, 1881

Braidwood introduced personal protective equipment for firefighters including a protective fire helmet, something so synonymous with firefighters today, it is difficult to imagine a time without it being standard issue.

These were all ideas he would bring to his next job.

A move to London

From January 1833, ten independent fire insurance company brigades merged to form the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE), and others joined them in the next few years. James Braidwood was appointed as the first Superintendent of the LFEE, bringing with him his excellent reputation for his training methods and successful leadership.

Understanding the man

“His great comforts were his family, his pipe, and the performance of his duty.”

An anonymous colleague of Braidwood’s at the LFEE shared with The Fireman magazine in 1881.

Braidwood in uniform ready to lead the London Fire Engine Establishment

Braidwood repeatedly demonstrated his bravery and expertise as a firefighter at scenes of several fires, where he successfully rescued those trapped by the flames.

He married widow Mary Ann Jane Jackson on 14 November 1838, at St. Mary Aldermary Church in the City of London. They surrounded themselves with a large family, as Jackson was a widow with five children which were then joined by six more. They lived at the LFEE Headquarters and fire station on Watling Street, City of London.

Firefighting in London

Braidwood began by primarily appointing ex-navy seaman as firefighters (known then as firemen). They were chosen as he believed they were best suited to working irregular duty patterns with very little time off. They were also familiar with drills and following orders.

A London Fire Engine Establishment firefighter in full uniform

They received a uniform and a protective fire helmet, less grand than those of the fire insurance company brigades but more functional. They were stationed across nineteen fire stations, located mostly in and around Central London, and organised into four districts each with a foreman in charge.

Despite the heavy workload, Braidwood insisted on regular training for his men. In Edinburgh this had been carried out at 4am to get his men used to working in the dark, without interruptions from bystanders. It can be assumed this followed in London on at least some occasions.

Innovations and tactics

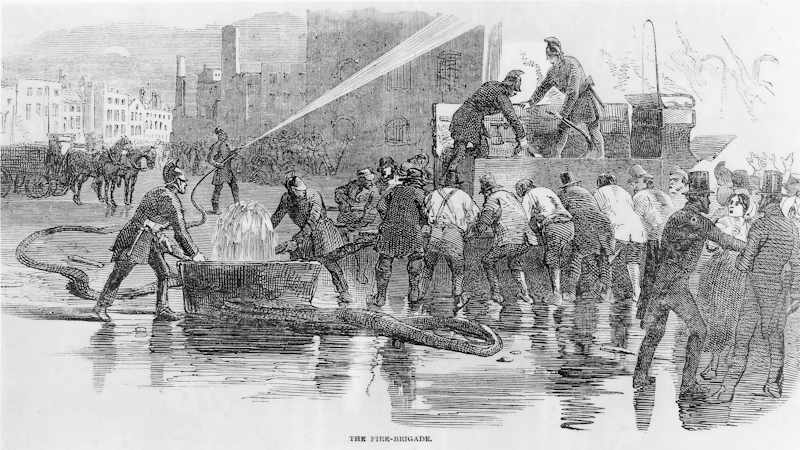

A manual pump is worked by volunteers, while firefighters from the LFEE direct their efforts to fight the fire

A key tactic introduced by Braidwood required firefighters to enter into a building on fire to find and tackle the source of the fire directly, rather than just applying water from the outside. He also insisted on his firefighters working as a team, at least two men went in together in a burning building to assist one another if one had any difficulties.

He worked together with two key manufacturers, Merryweather and Tilley, to introduce the London brigade manual fire engine, and a hose connector which was adopted by the London dockyards and the Royal Navy.

Initially Braidwood was resistant to the idea of steam fire engines, the next innovation in increasing water pumping capacity. It was not until 1860 that they were introduced into the LFEE fleet. Horses pulled the engine, which had a boiler and two steam pumps allowing the steam to pump to do the work, rather than the firefighter.

The Houses of Parliament on fire

In 1834 a great fire broke out at the Houses of Parliament. It started in a store of tally sticks (an early form of keeping accounts) which had been disposed of carelessly by a clerk.

'The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834' by JWM Turner 1835 [Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art]

When Braidwood, arrived alongside 64 firefighters and 12 fire engines, he realised that the old Houses could not be saved. The firefighters concentrated their efforts on trying to save Westminster Hall.

After the incident, Braidwood investigated why the fire was so destructive and listed his findings. This was primarily due to the materials it was made of, including timber and plaster, which had been highlighted as a fire risk before the fire.

The Tooley Street Fire

'A View of the Great Fire in Southwark: From London Bridge!' Wood engraving, first published in 1861 by S Marks and Sons

Several very serious fires had tested the resources of the LFEE before this significant fire broke out on the 22 June 1861 in Tooley Street, Bermondsey. The fire spread rapidly to the adjoining warehouses and took over two days to bring under control and a further two weeks to totally extinguish. See our Tooley Street fire article for more details.

There was sadly a great loss during this incident. Braidwood had noticed firefighters tackling the blaze were becoming tired and went over to cheer them on to lift their spirits. While he was assisting one of his firefighters, the front section of a warehouse collapsed on top of him, killing him instantly. It was three days before firefighters were able to recover his body due to the intensity of the flames.

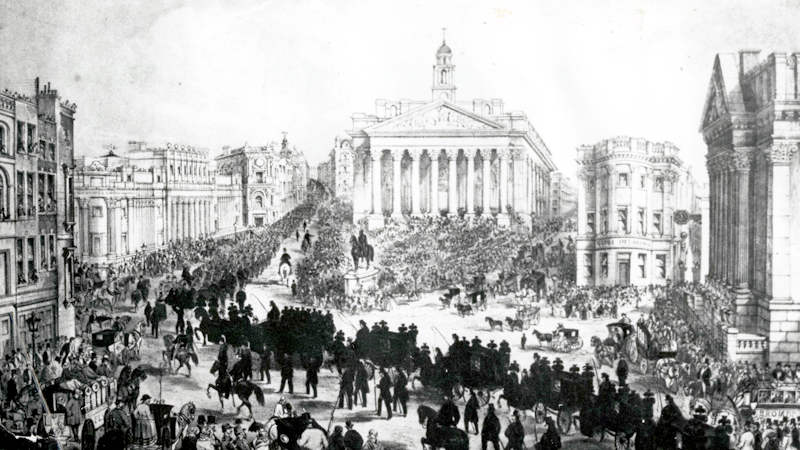

Engraving titled 'The funeral procession of the late Mr James Braidwood'

All London mourned. Braidwood was given a public funeral, and it is reported that the procession that followed it was a mile and half long, made up not just of dignitaries but also by ordinary Londoners. As a mark of respect, churches across the city rang their bells.

Braidwood's damaged shoulder epaulettes were saved and his tunic buttons were mounted in memorial

Braidwood was buried at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington alongside other members of his family, including his wife Mary, and also his step-son Thomas Jackson, a firefighter who also died on duty, six years before Braidwood.

The origins of a public fire service

Following this tragic incident, the fire insurance companies, who funded the LFFE, outlined some key factors and challenges effecting their ability to fight fires in London.

As London had expanded, and the potential fire hazards increased, the lack of reliable water supplies became a critical issue. Hydrants were non-existent or difficult to operate in some areas. A universal, reliable system of modern hydrants wasn’t resolved until later in the century.

In 1862, the insurance companies wrote to the then Home Secretary stating they could no longer be responsible for the fire safety of London. This was something that should become a public authority.

The Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act was passed in 1865, and from 1 January 1866 the Metropolitan Fire Brigade commenced as a public service.

Braidwood's lasting legacy

Captain Sir Eyre Massey Shaw became the next Superintendent of the LFEE in 1861, building on the legacy of Braidwood’s contribution to firefighting.

Laying flowers at the Braidwood's grave in Abney Park Cemetery

Superintendent Braidwood's final act had been to gallantly support his firefighters - but more than that, he had been a true trailblazer who revolutionised the fire services in London, and Edinburgh. From providing formal training for firefighters, to understanding the importance of knowing the details of how different types of building structures and materials are effected when on fire. He was clear about his vision of what made an effective firefighter and how fires should be fought.

This article was researched and written by museum volunteer Alan F.